The little cities of black diamonds are made up of a dozen or so small coal mining towns located in rural south eastern Ohio and they are the bones of what was once a booming coal industry now plagued with poverty and a dying population.

The little cities of black diamonds are made up of a dozen or so small coal mining towns located in rural south eastern Ohio and they are the bones of what was once a booming coal industry now plagued with poverty and a dying population.

A few of these forgotten small towns have historical significance and are a testimony of good times gone by, such as Rendville, San Toy, and Shawnee. I have blogged about San Toy (here) and I thought I would share some history about Rendville and few photos from a recent visit there.

It’s a tiny town with a big history, and although not much is left today I thought it would be interesting to share some recent photos of surviving structures and artifacts, as well as some history.

The stone staircase that once led up to the school is still pretty much intact, as well as a few of the historical buildings including the Rendville Art Works and the bones from the old School.

The stone staircase that once led up to the school is still pretty much intact, as well as a few of the historical buildings including the Rendville Art Works and the bones from the old School.

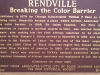

Some History: Rendville, Breaking the Color Barrier

Established in 1879 by Chicago industrialist William P. Rend as a coal mining town, Rendville became a place where African Americans broke the color barrier. In 1888, Dr. Isaiah Tuppins, the first African American to receive a medical degree in Ohio, was elected Rendville’s mayor, also making him the first African American to be elected a mayor in Ohio. Richard L. Davis arrived in Rendville in 1882 and became active in the Knights of Labor. He was one of the labor organizers from the Little Cities of Black Diamonds region who helped found the United Mine Workers of America in 1890. An outstanding writer and orator, Davis was elected to UMWA’s national executive board and organized thousands of African Americans and immigrants to join the union.

Adam Clayton Powell, Sr., another African-American miner, arrived in Rendville in 1884. In his own words, “sacrificed to the demon of gambling” in this “most lawless and ungodly place,” Powell had a spiritual awakening at the Rendville Baptist Church. He later went on to become the minister of one of the nation’s largest Protestant congregations, the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, New York City. He led the struggle against racism as a founder of the National Urban League and as a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and was an influential spiritual leader during the Harlem Renaissance. Roberta Preston was appointed postmaster of Rendville in 1963, becoming the first African American woman in Ohio to hold such a position. Following in her footsteps was Sophia Mitchell who became Ohio’s first African American woman mayor when she became Rendville’s mayor in 1969.

Excerpt from a news article:

Rendville, population 36 by the latest census count, is the smallest village in Ohio, but one with a rich legacy in the civil-rights and labor movements.

Rendville, population 36 by the latest census count, is the smallest village in Ohio, but one with a rich legacy in the civil-rights and labor movements.

The quiet of Rendville’s block-long downtown in the hills of southeastern Perry County is broken only by the whistle of the coal trains that still travel alongside Rt. 13.

Many of the people who live in the small collection of tidy clapboard houses in town are well into their years.

Asked if she is the eldest, Lenora “Babe” Jackson, 88, paused to think as the aroma of the pinto beans and corn bread she had prepared for dinner rose from her kitchen stove. “I’m the oldest since Ruel Harris died,” she said after a moment. “He was 93.”

Jackson started life here and will end life here, if she can. “Sometimes, people ask me, ‘Why are you still there?’ I say, ‘I like it.’ I want to stay here till I die. Don’t put me in a rest home.

“I miss a lot of the people that used to be here. A lot of them are dead.”

The village must live on, no matter how small it is, say residents and others who have taken an interest in Rendville.

With a population of about 1,000 people at its height during the boom years of the 1880s,

Rendville was home to black miners who lived and worked alongside white immigrant miners who were newly arrived from central and eastern Europe.

The town was named for William P. Rend, a Chicago industrialist who operated a coal mine here and paid black and white miners the same wages. The town was filled with saloons and gambling, and stores and churches. It hosted a big Emancipation Day celebration every year to commemorate President Abraham Lincoln’s ending of slavery in the South.

Adam Clayton Powell Sr. was a hard-living miner here in the 19th century before he surrendered his vices and was “saved” at a religious revival at the local First Baptist Church. He later became pastor of Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood and a civil-rights leader.

Richard L. Davis, another black coal miner, was an organized-labor leader in the Knights of Labor and then the United Mine Workers of America in the late 1800s. He worked to make sure that black miners had the same opportunities as white miners. He is buried in Rendville Cemetery.

“It is because of its significant history that there is value in maintaining the village,” said John Winnenberg, whose nonprofit development corporation, Sunday Creek Associates, based in nearby Shawnee, is helping to restore and promote the region.

Rendville is among the former coal-mining communities in Perry, Athens, Hocking and Morgan counties known collectively as the Little Cities of Black Diamonds.

The coal boom that began in the 1870s was bust by the 1930s, and the glory days of Rendville are long gone.

The coal boom that began in the 1870s was bust by the 1930s, and the glory days of Rendville are long gone.

The village will better preserve its identity and history if it stays incorporated rather than dissolving and being absorbed into surrounding Monroe Township, said Winnenberg, whose German-immigrant grandparents ran a grocery in Rendville in the late 1880s.

Mayor Bryan Bailey also wants the village to remain as it is. “It’s such a peaceful little town,” he said. “It’s a quiet piece of heaven.”

Bailey, 41, grew up here and lives at the family “home place” caring for his mother, 81-year-old Orpah Bailey, who is on the Village Council.

“We’re so small, we don’t spend a lot of money. If a road needs patching or graveling, we’ll do it ourselves,” said Mayor Bailey, who is self-employed and does welding and fabricating, excavation, trenching and hauling work.

do it ourselves,” said Mayor Bailey, who is self-employed and does welding and fabricating, excavation, trenching and hauling work.

The county sheriff and the nearby Corning Volunteer Fire Department provide police and fire protection if it is ever needed. It seldom is.

The small size brings some challenges, though. The six-member Village Council is rarely at full strength because it’s hard to find and keep people willing to serve.

The most-recent state audit, covering 2008 and 2009, found inadequate record-keeping by the village government. County Auditor Teresa Stevenson sent village fiscal officer Kathie Renick a letter last month admonishing her for not having submitted the village budget since 2007.

The village operates on little money. Its general-fund budget is approximately $4,700, Stevenson said.

As the population dwindles, others are stepping in to help keep the village going.

The church where Powell Sr. was saved from sin now is Rendville Art Works, where developmentally disabled people paint and sculpt.

The church where Powell Sr. was saved from sin now is Rendville Art Works, where developmentally disabled people paint and sculpt.

Frans Doppen, a Dutch-born historian and professor of social-studies education at Ohio University, and his students raised money to erect a historic marker downtown last year.

He and his students are remodeling a vacant clapboard house next to the village hall for possible use as a small museum, welcome center or restaurant. Doppen also is writing a book about Davis, the labor leader.

The mayor appreciates the efforts of Doppen and his students and said their work is the latest chapter in the story of Rendville.

Follow me on Social Media